THE TEMPEST ROLLING STONE INTERVIEW

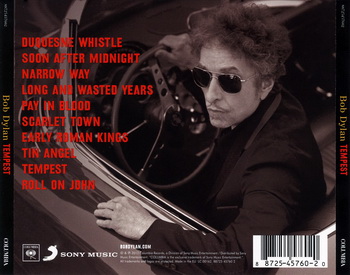

“I’m trying to explain something that can’t be explained,” says Bob Dylan. “Help me out.” It’s a midsummer day, an hour or so before evening, and we are seated at a table on a shaded patio, at the rear of a Santa Monica restaurant. Dylan is dressed warmer than the Southern California weather invited, in a buttoned black leather jacket over a thick white T-shirt. He also wears a ski cap — black around its lower half, white at its dome — pulled down over his ears and low on his forehead. A fringe of moptop-style reddish-blond hair, clearly a wig, curls slightly out from the front of the cap, above his eyebrows. He has a glass of cold water in front of him. ✽ In the 15 years since his 1997 album, Time Out of Mind, Dylan — who is now 71 — has enjoyed the most sustained period of creativity of his lifetime. His new album, Tempest, tells tales of mortal ends, moral faithlessness and hard-earned (if arbitrary) grace, culminating in a swirling, 14-minute epic about the Titanic, which mixes fact and fantasy, followed by a loving, mystical song about his late friend and peer John Lennon. It’s unlikely, though, that Dylan will ever eclipse the renown of his explosion of music and style in the 1960s, which transformed him into a definitive mythic force of those times. But Dylan wasn’t always comfortable with the effects of that reputation. In 1966, following a series of mind-blazing and controversial electric performances, the young hero removed himself from his own moment after he was laid low by a motorcycle accident, in Woodstock. The music that he returned with, in the late 1960s — John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline — sounded as if Dylan had become a different man. In truth, he now says, that’s what he was — or rather, what he was becoming. What Bob Dylan believes really happened to him after he survived his radical pinnacle is much more transformational than he has fully revealed before. This was an incident he’d alluded to briefly in his 2004 autobiography, Chronicles: Volume One, but in this interview the matter took on deeper implications.

At moments, I pushed in on some questions, and Dylan pushed back. We continued the conversation over the next many days, on the phone and by way of some written responses. Dylan didn’t hedge or attempt to guard himself as we went along. Just the opposite: He opened up unflinchingly, with no apologies. This is Bob Dylan as you’ve never known him before.

Do you see Tempest as an eventful album, like Time Out of Mind or Love and Theft?

Tempest was like all the rest of them: The songs just fall together. It’s not the album I wanted to make, though. I had another one in mind. I wanted to make something more religious. That takes a lot more concentration — to pull that off 10 times with the same thread — than it does with a record like I ended up with, where anything goes and you just gotta believe it will make sense.

Nonetheless, this seems among your bigger works, like Time Out of Mind, though more outward, less inward.

Well . . . the Time Out of Mind record, that was the beginning of me making records for an audience that I was playing to night after night. They were different people from different walks of life, different environments and ages. There was no reason for these new people to hear songs I’d written 30 years earlier for different purposes. If I was going to continue on, what I needed were new songs, and I had to write them, not necessarily to make records, but to play for the public.

The songs on Time Out of Mind weren’t meant for somebody to listen to at home. Most of the songs work, whereas before, there might have been better records, but the songs don’t work. So I’ll stick with what I was doing after Time Out of Mind, rather than what I was doing in the Seventies and Eighties, where the songs just don’t work.

That album was plainly received as a turning point. It began a sustained winning streak. Everything since then is a body of work that can stand on its own.

I hope it can. It should connect with people. The thing about it is that there is the old and the new, and you have to connect with them both. The old goes out and the new comes in, but there is no sharp borderline. The old is still happening while the new enters the scene, sometimes unnoticed. The new is overlapping at the same time the old is weakening its hold. It goes on and on like that. Forever through the centuries. Sooner or later, before you know it, everything is new, and what happened to the old? It’s like a magician trick, but you have to keep connecting with it.

It’s just like when talking about the Sixties. If you were here around that time, you would know that the early Sixties, up to maybe ’64, ’65, was really the Fifties, the late Fifties. They were still the Fifties, still the same culture, in America anyway. And it was still going strong but fading away. By ’66, the new Sixties probably started coming in somewhere along that time and had taken over by the end of the decade. Then, by the time of Woodstock, there was no more Fifties. I really wasn’t so much a part of what they call “the Sixties.”

Even though you’re so identified with it?

Evidently I was, and maybe even still am. I was there during that time, but I really couldn’t identify with what was happening. It didn’t mean that much to me. I had my own family by then. You know, for instance, [Timothy] Leary and others like him, they wouldn’t have lasted a second in earlier days. Of course, the Vietnam War didn’t help any.

Do you ever worry that people interpreted your work in misguided ways? For example, some people still see “Rainy Day Women” as coded about getting high.

It doesn’t surprise me that some people would see it that way. But these are people that aren’t familiar with the Book of Acts.

Sometimes you seem to have a distaste for the 1960s.

The Fifties were a simpler time, at least for me and the situation I was in. I didn’t really experience what a lot of the other people my age experienced, from the more mainstream towns and cities. Where I grew up was as far from the cultural center as you could get. It was way out of the beaten path. You had the whole town to roam around in, though, and there didn’t seem to be any sadness or fear or insecurity. It was just woods and sky and rivers and streams, winter and summer, spring, autumn. The changing of the seasons. The culture was mainly circuses and carnivals, preachers and barnstorming pilots, hillbilly shows and comedians, big bands and whatnot. Powerful radio shows and powerful radio music. This was before supermarkets and malls and multiplexes and Home Depot and all the rest. You know, it was a lot simpler. And when you grow up that way, it stays in you. Then I left, which was, I guess, toward the end of the Fifties, but I saw and felt a lot of things in the Fifties, which generates me to this day. It’s sort of who I am.

I guess the Fifties would have ended in about ’65. I don’t really have a warm feeling for that period of time. Why would I? Those days were cruel.

Why is that? Was it just too much upheaval, being at the white-hot center of it?

Yeah, that and a whole lot of other stuff. Things were beginning to get corporatized. That wouldn’t have mattered to me, but it was happening to the music, too. And I truly loved the music. I saw the death of what I love and a certain way of life that I’d come to take for granted.

Yet people thought your music spoke to and reflected the 1960s. Do you feel that’s also the case with your music since 1997?

Sure, my music is always speaking to times that are recent. But let’s not forget human nature isn’t bound to any specific time in history. And it always starts with that. My songs are personal music; they’re not communal. I wouldn’t want people singing along with me. It would sound funny. I’m not playing campfire meetings. I don’t remember anyone singing along with Elvis, or Carl Perkins, or Little Richard. The thing you have to do is make people feel their own emotions. A performer, if he’s doing what he’s supposed to do, doesn’t feel any emotion at all. It’s a certain kind of alchemy that a performer has.

Don’t you think you’re a particularly American voice – for how your songs reference our history, or have commented on it?

They’re historical. But they’re also biographical and geographical. They represent a particular state of mind. A particular territory. What others think about me, or feel about me, that’s so irrelevant. Any more than it is for me, when I go see a movie, say, Wuthering Heights or something, and have to wonder what’s Laurence Olivier really like. When I see an actor on the stage or something, I don’t think about what they’re like. I’m there because I want to forget about myself, forget about what I care or do not care about. Entertaining is a type of sport.

[Dylan suddenly seems excited.]

Let me show you something. I want to show you something. You might be interested in this. You might take this someplace. You might want to rephrase your questions, or think of new ones [laughs]. Let me show you this. [Gets up and walks to another table.]

You want me to come with you?

No, no, no, I got it right here. I thought this might interest you. [Brings a weathered paperback to the table.] See this book? Ever heard of this guy? [Shows me “Hell’s Angel: The Life and Times of Sonny Barger and the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club,” by Sonny Barger.]

Yeah, sure.

He’s a Hells Angel.

He was “the” Hells Angel.

Look who wrote this book. [Points at coauthors’ names, Keith Zimmerman and Kent Zimmerman.] Do those names ring a bell? Do they look familiar? Do they? You wonder, “What’s that got to do with me?” But they do look familiar, don’t they? And there’s two of them there. Aren’t there two? One’s not enough? Right? [Dylan’s now seated, smiling.] I’m going to refer to this place here. [Opens the book to a dog-eared page.] Read it out loud here. Just read it out loud into your tape recorder.

“One of the early presidents of the Berdoo Hells Angels was Bobby Zimmerman. On our way home from the 1964 Bass Lake Run, Bobby was riding in his customary spot — front left — when his muffler fell off his bike. Thinking he could go back and retrieve it, Bobby whipped a quick U-turn from the front of the pack. At that same moment, a Richmond Hells Angel named Jack Egan was hauling ass from the back of the pack toward the front. Egan was on the wrong side of the road, passing a long line of speeding bikes, just as Bobby whipped his U-turn. Jack broadsided poor Bobby and instantly killed him. We dragged Bobby’s lifeless body to the side of the road. There was nothing we could do but to send somebody on to town for help.” Poor Bobby.

Yeah, poor Bobby. You know what this is called? It’s called transfiguration. Have you ever heard of it?

Yes.

Well, you’re looking at somebody.

That . . . has been transfigured?

Yeah, absolutely. I’m not like you, am I? I’m not like him, either. I’m not like too many others. I’m only like another person who’s been transfigured. How many people like that or like me do you know?

By transfiguration, you mean it in the sense of being transformed? Or do you mean transmigration, when a soul passes into a different body?

Transmigration is not what we are talking about. This is something else. I had a motorcycle accident in 1966. I already explained to you about new and old. Right? Now, you can put this together any way you want. You can work on it any way you want. Transfiguration: You can go and learn about it from the Catholic Church, you can learn about it in some old mystical books, but it’s a real concept. It’s happened throughout the ages. Nobody knows who it’s happened to, or why. But you get real proof of it here and there. It’s not like something you can dream up and think. It’s not like conjuring up a reality or like reincarnation — or like when you might think you’re somebody from the past but have no proof. It’s not anything to do with the past or the future. So when you ask some of your questions, you’re asking them to a person who’s long dead. You’re asking them to a person that doesn’t exist. But people make that mistake about me all the time. I’ve lived through a lot. Have you ever heard of a book called No Man Knows My History? It’s about Joseph Smith, the Mormon prophet. The title could refer to me. Transfiguration is what allows you to crawl out from under the chaos and fly above it. That’s how I can still do what I do and write the songs I sing and just keep on moving.

When you say I’m talking to a person that’s dead, do you mean the motorcyclist Bobby Zimmerman, or do you mean Bob Dylan?

Bob Dylan’s here! You’re talking to him.

Then your transfiguration is . . .

It is whatever it is. I couldn’t go back and find Bobby in a million years. Neither could you or anybody else on the face of the Earth. He’s gone. If I could, I would go back. I’d like to go back. At this point in time, I would love to go back and find him, put out my hand. And tell him he’s got a friend. But I can’t. He’s gone. He doesn’t exist.

OK, so when you speak of transfiguration . . .

I only know what I told you. You’ll have to go and do the work yourself to find out what it’s about.

I’m trying to determine whom you’ve been transfigured from, or as.

I just showed you. Go read the book.

That’s who you have in mind? What could the connection to that Bobby Zimmerman be other than the name?

I don’t have it in mind. I didn’t write that book. I didn’t make it up. I didn’t dream that. I’m not telling you I had a dream last night. Remember the song “Last Night I Had the Strangest Dream”? I didn’t write that, either. I’m showing you a book that’s been written and published. I mean, look at all the connecting things: motorcycles, Bobby Zimmerman, Keith and Kent Zimmerman, 1964, 1966. And there’s more to it than even that. If you went to find this guy’s family, you’d find a whole bunch more that connected. I’m just explaining it to you. Go to the grave site.

When did you come across this book?

Uh, you know. . . . When did I come across that book? Somebody put it in my hand years ago. I’d met Sonny Barger in the Sixties, but didn’t know him very well. He was friends with Jerry Garcia. Maybe I saw it on a bookshelf out there and the bookseller slipped it into my hand. But I began to read it, and I thought I was reading about Sonny, but then I got to that part and realized it wasn’t about him at all. I didn’t even really check the authors’ names until later and that blew my mind, too.

About a year later, I went to a library in Rome and I found a book about transfiguration, because it’s nothing you really hear about every day, and it’s in that mystical realm, and I found out only enough to know that, uh, OK, I’m not an authority on it, but it kind of sets you straight on what sets you apart.

I’d always been different than other people, but this book told me why. Like certain people are set apart. You know, it’s just like the phrase, “peers” – I mean, I see this, “Well, your peers this, your peers that.” And I’ve always wondered, who are my peers? When I received the Medal of Freedom I started thinking more about it. Like, who are they? But then it became clear. My peers are Aretha Franklin, Duke Ellington, B.B. King, John Glenn, Madeleine Albright, Pat Summitt, Toni Morrison, Jasper Johns, Martha Graham, Sidney Poitier. People like that, and they are set apart, too. And I’m proud to be counted among them.

You don’t write the kind of songs I write just being a conventional type of songwriter. And I don’t think anybody will write them like this again, any more than anybody will ever write a Hank Williams or Irving Berlin song. That’s pretty much for sure. I just think I’ve taken things to a new level because I’ve had to. Because I’ve been forced to. You have to constantly reshape things because everything keeps expanding on you. Life has a way of spreading out.

Why do you have that need to constantly reshape things?

Because that’s the nature of existence. Nothing stays where it is for very long. Trees grow tall, leaves fall, rivers dry up and flowers die. New people are born every day. Life doesn’t stop.

Is that part of what touring is about for you?

Touring is about anything you want it to be about. Is there something strange about touring? About playing live shows? If there is, tell me what it is. Willie [Nelson]’s been playing them for years, and nobody ever asks him why he still tours. Look, you travel to different places and you encounter things that you might not encounter every day if you stayed home. And you get to play music for the people – all of the people, every nationality and in every country. Ask any performer or entertainer that does this, they’ll all tell you the same thing. That they like doing it and that it means a lot to people. It’s just like any other line of work, only different.

Yet for a long time, from 1966 to 1974, you left touring behind. Did you always expect to return to live performance, as part of doing what it is that you do?

I know I left it behind, but then I picked it up again. Things change. Also, there are performers that don’t go on the road. They might go to Vegas and just stay there. You could do it that way — who knows, I may do that too, someday. There are a lot of worse ways to end up. It’s always been this way for everybody who’s ever done it, going back to those ancient days. The carnival came to town, the carnival left and you ran off with them. It’s just what you did. You don’t travel to the end of the line until someone gives you a gold watch and a pat on the back. That’s not the way the game works. People really don’t retire. They fade away. They run out of steam. People aren’t interested in them anymore.

What do you think of Bruce Springsteen? U2?

I love Bruce like a brother. He’s a powerful performer — unlike anybody. I care about him deeply. U2’s a force to be reckoned with. Bono’s energy has far-reaching effects, and in some ways, he’s his own tempest.

Miles Davis had this idea that music was best heard in the moments in which it was performed — that that’s where music is truly alive. Is your view similar?

Yeah, it’s exactly the same as Miles’ is. We used to talk about that. Songs don’t come alive in a recording studio. You try your best, but there’s always something missing. What’s missing is a live audience. Sinatra used to make records like that — used to bring people into the studio as an audience. It helped him get into the songs better.

So live performance is a purpose you find fulfilling?

If you’re not fulfilled in other ways, performing can never make you happy. Performing is something you have to learn how to do. You do it, you get better at it and you keep going. And if you don’t get better at it, you have to give it up. Is it a fulfilling way of life? Well, what kind of way of life is fulfilling? No kind of life is fulfilling if your soul hasn’t been redeemed.

You’ve described what you do not as a career but as a calling.

Everybody has a calling, don’t they? Some have a high calling, some have a low calling. Everybody is called but few are chosen. There’s a lot of distraction for people, so you might not never find the real you. A lot of people don’t.

How would you describe your calling?

Mine? Not any different than anybody else’s. Some people are called to be a good sailor. Some people have a calling to be a good tiller of the land. Some people are called to be a good friend. You have to be the best at whatever you are called at. Whatever you do. You ought to be the best at it — highly skilled. It’s about confi dence, not arrogance. You have to know that you’re the best whether anybody else tells you that or not. And that you’ll be around, in one way or another, longer than anybody else. Somewhere inside of you, you have to believe that.

Some of us have seen your calling as somebody who has done his best to pay witness to the world, and the history that made that world.

History’s a funny thing, isn’t it? History can be changed. The past can be changed and distorted and used for propaganda purposes. Things we’ve been told happened might not have happened at all. And things that we were told that didn’t happen actually might have happened. Newspapers do it all the time; history books do it all the time. Everybody changes the past in their own way. It’s habitual, you know? We always see things the way they really weren’t, or we see them the way we want to see them. We can’t change the present or the future. We can only change the past, and we do it all the time.

There’s that old wisdom “History is written by the victors.”

Absolutely. And then there’s Henry Ford. He didn’t have much use for history at all.

But you have a use for it. In Chronicles, you wrote about your interest in Civil War history. You said that the spirit of division in that time made a template for what you’ve written about in your music. You wrote about reading the accounts from that time Reading, say, Grant’s remembrances is different than reading Shelby Foote’s History of the Civil War.

The reports are hardly the same. Shelby Foote is looking down from a high mountain, and Grant is actually down there in it. Shelby Foote wasn’t there. Neither were any of those guys who fight Civil War re-enactments. Grant was there, but he was off leading his army. He only wrote about it all once it was over. If you want to know what it was about, read the daily newspapers from that time from both the North and South. You’ll see things that you won’t believe. There is just too much to go into here, but it’s nothing like what you read in the history books. It’s way more deadly and hateful. There doesn’t seem to be anything heroic or honorable about it at all. It was suicidal. Four years of looting and plunder and murder done the American way. It’s amazing what you see in those newspaper articles. Places like the Pittsburgh Gazette, where they were warning workers that if the Southern states have their way, they are going to overthrow our factories and use slave labor in place of our workers and put an end to our way of life. There’s all kinds of stuff like that, and that’s even before the first shot was fired.

But there were also claims and rumors from the South about the North. . . .

There’s a lot of that, too, about states’ rights and loyalty to our state. But that didn’t make any sense. The Southern states already had rights. Sometimes more than the Northern states. The North just wanted them to stop slavery, not even put an end to it — just stop exporting it. They weren’t trying to take the slaves away. They just wanted to keep slavery from spreading. That’s the only right that was being contested. Slavery didn’t provide a working wage for people. If that economic system was allowed to spread, then people in the North were going to take up arms. There was a lot of fear about slavery spreading.

Do you see any parallels between the 1860s and present-day America?

Mmm, I don’t know how to put it. It’s like . . . the United States burned and destroyed itself for the sake of slavery. The USA wouldn’t give it up. It had to be grinded out. The whole system had to be ripped out with force. A lot of killing. What, like, 500,000 people? A lot of destruction to end slavery. And that’s what it really was all about. This country is just too fucked up about color. It’s a distraction. People at each other’s throats just because they are of a different color. It’s the height of insanity, and it will hold any nation back — or any neighborhood back. Or any anything back. Blacks know that some whites didn’t want to give up slavery — that if they had their way, they would still be under the yoke, and they can’t pretend they don’t know that. If you got a slave master or Klan in your blood, blacks can sense that. That stuff lingers to this day.

Just like Jews can sense Nazi blood and the Serbs can sense Croatian blood. It’s doubtful that America’s ever going to get rid of that stigmatization. It’s a country founded on the backs of slaves. You know what I mean? Because it goes way back. It’s the root cause. If slavery had been given up in a more peaceful way,America would be far ahead today. Whoever invented the idea “lost cause. . . . ” There’s nothing heroic about any lost cause. No such thing, though there are people who still believe it.

Did you hope or imagine that the election of President Obama would signal a shift, or that it was in fact a sea change?

I don’t have any opinion on that. You have to change your heart if you want to change.

Since his election, there’s been a great reaction by some against him.

They did the same to Bush, didn’t they? They did the same thing to Clinton, too, and Jimmy Carter before that. Look what they did to Kennedy. Anybody who’s going to take that job is going to be in for a rough time.

Don’t you think some of the reaction has stemmed from that kind of racial resonance you were talking about?

I don’t know. I don’t know, but I don’t think that’s the same thing. I have no idea what they are saying for or against him. I really don’t. I don’t know how deep it goes or how shallow it is.

You are aware that he’s been branded as un-American or a socialist

You can’t pay any attention to that kind of stuff, as if you’ve never heard those kind of words before. Eisenhower was accused of being un-American. And wasn’t Nixon a socialist? Look what he did in China. They’ll say bad things about the next guy, too.

So you don’t think some of the reaction against Obama has been in reaction to the event that a black man has become president of the United States?

Do you want me to repeat what I just said, word for word? What are you talking about? People loved the guy when he was elected. So what are we talking about? People changing their minds? Well, who are these people that changed their minds? Talk to them. What are they changing their minds for? What’d they vote for him for? They should’ve voted for somebody else if they didn’t think they were going to like him.

The point I’m making is that perhaps lingering American resentments about race are resonant in the opposition to President Obama, which has not been a quiet opposition.

You mean in the press? I don’t know anybody personally that’s saying this stuff that you’re just saying. The press says all kinds of stuff. I don’t know what they would be saying. Or why they would be saying it. You can’t believe what you read in the press anyway.

Do you vote?

Uh . . .

Should we do that? Should we vote?

Yeah, why not vote? I respect the voting process. Everybody ought to have the right to vote. We live in a democracy. What do you want me to say? Voting is a good thing.

I was curious if you vote.

[Smiling] Huh?

What’s your estimation of President Obama been when you’ve met him?

What do I think of him? I like him. But you’re asking the wrong person. You know who you should be asking that to? You should be asking his wife what she thinks of him. She’s the only one that matters. Look, I only met him a few times. I mean, what do you want me to say? He loves music. He’s personable. He dresses good. What the fuck do you want me to say?

You live in these times, you have reactions to various national ups and downs. Are you, for example, disappointed by the resistance the president has met with? Would you like to see him re-elected?

I’ve lived through a lot of presidents! And you have too! Some are re-elected and some aren’t. Being re-elected isn’t the mark of a great president. Sometimes the guy you get rid of is the guy you wish you had back.

I’ve brought up the subject partly because of something you said the night he was elected: “It looks like things are gonna change now.” Do you feel that the change you anticipated has been borne out?

You want to repeat that again? I have no idea what I said.

It was Election Night 2008. Onstage at the University of Minnesota, introducing your band’s members, you indicated your bassist and said, “Tony Garnier, wearing the Obama button. Tony likes to think it’s a brand-new time right now. An age of light. Me, I was born in 1941 – that’s the year they bombed Pearl Harbor. Well, I been living in a world of darkness ever since. But it looks like things are gonna change now.”

I don’t know what I said or didn’t say. As far as Tony goes, yeah, maybe he was wearing an Obama button and maybe I said some stuff because right there in the moment it all made sense. Maybe I said things looked like they could change. And maybe they did change. I don’t think I could have predicted how they would change, but whatever was said, it was said for people in that hall for that night. You know what I’m saying? It wasn’t said to be played on a record forever. Or did I go down to the middle of town and give a speech?

It was onstage.

It was on the streets?

Stage. Stage.

OK. It was on the stage. I don’t know what I could have meant by that. You say things sometimes, you don’t know what the hell you mean. But you’re sincere when you say it. I would hope that things have changed. That’s all I can say, for whatever it is that I said. I’m not going to deny what I said, but I would have hoped that things would’ve changed. I certainly hope they have.

I get the impression when we talk that you’re reluctant to say much about the president or how he’s been criticized.

Well, you know, I told you what I could.

In that case, let’s return to Tempest. Can you talk a little about your songwriting method these days?

I can write a song in a crowded room. Inspiration can hit you anywhere. It’s magical. It’s really beyond me.

What about your role as a producer? How would you describe the sound that you were trying to achieve here?

The sound goes with the song. But that’s funny. Somebody was telling me that Justin Bieber couldn’t sing any of these songs. I said I couldn’t sing any of his songs either. And that person said, “Baby, I’m so grateful for that.”

There’s a fair amount of mortality, certainly in the last three songs – “Tin Angel,” “Tempest” and “Roll On John.” People come to hard endings.

The people in “Frankie and Johnny,” “Stagger Lee” and “El Paso” have come to hard endings, too, and definitely it’s that way in one of my favorite songs, “Delia.” I can name you a hundred songs where everything ends in tragedy. It’s called tradition, and that’s what I deal in. Traditional, with a capital T. Maybe people have to have a simplistic way of identifying something, if they can’t grasp it properly – use some term that they think they can understand, like mortality. Oh, like, “These songs must be about mortality. I mean, Dylan, isn’t he an old guy? He must be thinking about that.” You know what I say to that horseshit? I say these idiots don’t know what they’re talking about. Go find somebody else to pick on.

There’s plenty of death songs. You may well know, in folk music every other song deals with death. Everybody sings them. Death is a part of life. The sooner you know that, the better off you’ll be. That’s the only way to look at it. As far as agreeing with what the common consensus is of what my songs mean or don’t mean, it’s just foolish. I can’t really verify or not verify what other people say my songs are about.

It was interesting that in the aftermath of the Titanic sinking there were many folk and blues and country songs on the subject. Why do you think that was?

Folk musicians, blues musicians did write a lot of songs about the Titanic. That’s what I feel that I’m best at, being a folk musician or a blues musician, so in my mind it’s there to be done. If you’re a folk singer, blues singer, rock & roll singer, whatever, in that realm, you oughta write a song about the Titanic, because that’s the bar you have to pass.

Today we have so much media that before something happens, you see it. You know about it or you think you do. No one can tell you a thing. You don’t need a song about the fire that happened in China town last night because it was all over the news. In songs, you have to tell people about something they didn’t see and weren’t there for, and you have to do it as if you were. Nobody can contradict you on a song about the Titanic any more than they can contradict you on a song about Billy the Kid.

Those folk musicians, though, were people who never would’ve been let aboard the Titanic, or would’ve been in steerage.

No, but all the old country singers, country blues, hillbilly singers, rock & roll singers, what they all had in common was a powerful imagination. And I have that, too. It’s not that unusual for me to write a song about the Titanic tragedy any more than it was for Leadbelly. It might be unusual to write such a long ballad about it, but not necessarily about the disaster itself.

In some Titanic songs, there were those who saw the event as a judgment on modern times, on mankind for assuming that it could be unsinkable. Is there some of that in your song?

No, no, I try to stay away from all that stuff. I don’t imply any of it. I’m not interested in it. I’m just interested in showing you what happened, on the level that it happened on. That’s all. The meaning of it is beyond me.

You also have a song about John Lennon, “Roll On John,” on this album. What moved you to record this now?

I can’t remember — I just felt like doing it, and now would be as good a time as any. I wasn’t even sure that song fit on this record. I just took a chance and stuck it on there. I think I might’ve finished it to include it. It’s not like it was just written yesterday. I started practicing it late last year on some stages.

Lennon said that he was inspired by you, but also felt competitive with you. You and Lennon were cultural lions in the 1960s and 1970s. Did that ever make for unease or for a sense of competition in each other’s company?

I think we covered peers a while back, did we not? John came from the northern regions of Britain. The hinterlands. Just like I did in America, so we had some kind of environmental things in common. Both places were pretty isolated. Though mine was more landlocked than his. But everything is stacked against you when you come from that. You have to have the talent to overcome everything. That was something I had in common with him. We were all about the same age and heard the same exact things growing up. Our paths crossed at a certain time, and we both had faced a lot of adversity. We even had that in common. I wish that he was still here because we could talk about a lot of things now.

You went to visit Liverpool, where Lennon grew up. How long ago was that?

A couple years ago? Strawberry Field is right in back of his house. Didn’t know that. Evidently, he grew up with his aunt. He’d be out there in the Strawberry Field, a park behind his house that was fenced off. Being in Britain, there’s all this hanging history, chopping off heads. I mean, you grow up with that, if you’re a Brit. I didn’t quite understand the line about getting hung — “Nothing to get hung about” — well, time had moved on, it was like “hung up,” nothing to be hung up about. But he was speaking literally: “What are you doing out there, John?” “Don’t worry, Mum, nothing they’re going to hang me about, nothing to get hung about.” I found that kind of interesting.

In “Roll On John,” there’s a sense that Lennon was trapped in America, far away from home. Did you feel empathy for those experiences?

How could you not? There’s so much you can say about any person’s life. It’s endless, really. I just picked out stuff that I thought that I was close enough to, to understand.

I hear various sources and tributes in Tempest and your other recent music, including the sounds of Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, the spirit of Charley Patton. Do you think of yourself as a bluesman?

Bluesmen lead lives of great hardship. And I’ve got too much rock & roll in my blood to call myself a blues singer. Country blues, folk music and rock & roll make up the kind of music that I play.

I also hear echoes of Bing Crosby, going all the way back to “Nashville Skyline.” Does he bear influence for you?

A lot of people would like to sing like Bing Crosby, but very few could match his phrasing or depth of tone. He’s influenced every real singer whether they know it or not. I used to hear Bing Crosby as a kid and not really pay attention to him. But he got inside me nevertheless. Him and Nat King Cole were my father’s favorite singers, and those records played in our house.

You said that you originally wanted to make a more religious album this time — can you tell me more about that?

The songs on Tempest were worked out in rehearsals on stages during soundchecks before live shows. The religious songs maybe I felt were too similar to each other to release as an album. Someplace along the line, I had to go with one or the other, and Tempest is what I went with. I’m still not sure it was the right decision.

When you say religious songs . . .

Newly written songs, but ones that are traditionally motivated.

More like “Slow Train Coming”?

No. No. Not at all. They’re more like “Just a Closer Walk With Thee.”

From the 1980s on, there’s been a lot of dark territory in your songs. Has any of this been a reflection of an ongoing religious struggle for you?

Nah, I don’t have any of those religious struggles. I just showed you that book. Transfiguration eliminates all that stuff. You don’t have those kinds of struggles. You never did, and you never will. No. You have to amplify your faith. Those are struggles for other people. Other people that you don’t know and never will. Everybody’s facing some kind of struggle for sure.

Has your sense of your faith changed?

Certainly it has, o ye of little faith. Who’s to say that I even have any faith or what kind? I see God’s hand in everything. Every person, place and thing, every situation. I mean, we can have faith in just about anything. Can’t we? You might have faith in that bloody mary you’re drinking. It might quiet your nerves.

[Laughs] It’s water — not a bloody mary.

Well [laughs], it looks like a bloody mary to me. I’m gonna say that it is. I’ll rewrite your history for you.

You’ve been willing to talk about these matters before.

Yeah, but that was before and this is now. I have enough faith for me to be faithful to myself. Faith is good – it could move mountains. Not that bloody-mary faith that you have, but the kind of faith that people like me have. You can tell whether other people have faith or no faith by the way they behave, by the shit that comes out of their mouths. A little faith can go a long ways. It’s the right thing for people to have. When we have little else, that will do. But it takes a while to acquire it. You just got to keep looking.

Sometimes people have acquired it, then feel like they lose faith.

Yeah, absolutely. You get hit hard in life. People get hit with everything. We all do. We all get hit upside the head. And some of us get hit harder than others. Some of us get no chance at all. Some of us get more than one chance. No two are alike. You have to push on. Make the best of it. Just like the Woody Guthrie song “Hard Travelin’. ”

Clearly, the language of the Bible still provides imagery in your songs.

Of course, what else could there be? I believe in the Book of Revelation. I believe in disclosure, you know? There’s truth in all books. In some kind of way. Confucius, Sun Tzu, Marcus Aurelius, the Koran, the Torah, the New Testament, the Buddhist sutras, the Bhagavad-Gita, the Egyptian Book of the Dead, and many thousands more. You can’t go through life without reading some kind of book.

Time Out of Mind started with this image of somebody walking through streets that are dead.

A lot of walking in that record, right? I’ve heard that.

When that narrator talks about walking this or that road, do you have pictures of those roads in your mind?

Yeah, but not in a specific kind of way. You can feel it, without being able to see it. It’s an old-time thing: the walking blues.

The walking could be what somebody witnesses. It could be the road to death; it could be the road to illumination.

Sure, all those roads. How many roads must a man walk down? Not run down, drive down or crawl down? I’ve been raised on that. The walking blues. “Walking to New Orleans,” “Cadillac Walk,” “Hand Me Down My Walkin’ Cane.” It’s the only way I know. It comes natural.

The person who’s walking in these songs, is he walking alone?

Sometimes, but then again, sometimes not. Sometimes you got to get into your own space for a while. It never really dawns on me, though, whether I’m walking alone or not. Seems like I’m always walking with somebody.

In “Sugar Baby,” on “Love and Theft,” you sang, “Every moment of existence seems like some dirty trick.” Did these words convey a significant change from how you may have felt before?

No, there’s been no change whatsoever. I used to think most people felt that way about existence, and I still think that.

I want to know more about the matter of transfiguration. Is there a specific moment in which you became aware of it?

Yeah, I can refer you to the book [the Sonny Barger biography]. It happens gradually. I’d say that that accident, however, if you want to call it that, I think that was about ’64? [Referring to the death of Bobby Zimmerman, which, in fact, took place in 1961.] As I said earlier, I had a motorcycle accident myself, in ’66, so we’re talking maybe about two years — a gradual kind of slipping away, and, uh, some kind of something else appearing out of nowhere.

And it makes perfect sense, because in the truth world, nothing does begin or end. You know, it’s like things begin while something else is ending. There’s never any sharp borderline or dividing line. We’ve talked about this. You know how we have dividing lines between countries. We have boundaries. Well, boundaries in the cosmological world don’t really exist, any more than they do between night and day.

After your motorcycle accident, you were in some ways a different person?

I’m trying to explain something that can’t be explained. Help me out. Read the pages of the book. Some people never really develop into who they’re supposed to be. They get cut off. They go off another way. It happens a lot. We all see people that that’s happened to. We see them on the street. It’s like they have a sign hanging on them.

Did you have an inkling of this before you read the Barger book?

I didn’t know who I was before I read the Barger book.

Here’s one way of looking at this: In the 1960s, people saw you as a revolutionary fireball up until the motorcycle accident. Afterward, with the music made in Woodstock with the Band, and with “John Wesley Harding” and “Nashville Skyline,” some were bewildered by your transformation. You came back from that hiatus looking different, sounding different, in voice, music and words.

Why is it that when people talk about me they have to go crazy? What the fuck is the matter with them? Sure, I had a motorcycle accident. Sure, I played with the Band. Yeah, I made a record called John Wesley Harding. And sure, I sounded different. So fucking what? They want to know what can’t be known. They are searching — they are seekers. Like in the Pete Townshend song where he’s trying to find his way to 50 million fables. For what? Why are they doing this? They don’t really know. It’s sad. It really is. May the Lord have mercy on them. They are lost souls. They really don’t know. It’s sad – it really is. It’s sad for me, and it’s sad for them.

Why do you think that is the case?

I don’t have a clue. If you ever find out, come and tell me.

Are you saying that you can’t really be known?

Nobody knows nothing. Who knows who’s been transfigured and who has not? Who knows? Maybe Aristotle? Maybe he was transfigured? I can’t say. Maybe Julius Caesar was transfigured. I have no idea. Maybe Shakespeare. Maybe Dante. Maybe Napoleon. Maybe Churchill. You just never know, because it doesn’t figure into the history books. That’s all I’m saying.

Sometimes we can deepen ourselves or give aid to other people by trying to know them.

If we’re responsible to ourselves, then we can be responsible for other people, too. But we have to know ourselves first. People listen to my songs and they must think I’m a certain type of way, and maybe I am. But there’s more to it than that. I think they can listen to my songs and figure out who they are, too.

When you say that those who conjecture about you don’t really know what they’re talking about, does that mean that you feel misunderstood?

It doesn’t mean that at all! [Laughs] I mean, what’s there, like, to understand? I mean – no, no. Just the opposite. Who’s supposed to understand? My in-laws? Am I supposed to be some misunderstood artist living in an attic? You tell me. What’s there to understand? Please, can we stop now?

With this sort of question? Just one more: In the past 10 years, you’ve written an autobiography; there was a fictional film biography, I’m Not There; and there was Martin Scorsese’s documentary, No Direction Home – three big attempts to come to terms with your history, the biggest being your book, Chronicles. Wasn’t that, in a way, an attempt to explain certain things about your life?

If you read Chronicles, you know it doesn’t attempt to be any more than what it is. You’re not going to find the meaning of life in it. Mine or anyone else’s. And if you’ve seen No Direction Home, you might have noticed that it ended in ’66. And I’m Not There — I don’t know anything about that movie. All I know is they licensed about 30 of my songs for it.

Did you like I’m Not There?

Yeah, I thought it was all right. Do you think that the director was worried that people would understand it or not? I don’t think he cared one bit. I just think he wanted to make a good movie. I thought it looked good, and those actors were incredible.

I think the movie grew from a long-stated perception of you as somebody with a lot of phases and identities.

I don’t see myself that way. But what does it matter? It’s only a movie.

In Chronicles, you wrote about declining to write songs for a 1971 play by Archibald MacLeish because you thought the play, Scratch, “spelled death for society with humanity lying facedown in its own blood.” Wouldn’t that same vision apply to the 2003 film you co-wrote, Masked and Anonymous?

Uh, yeah. You could look at it that way.

Were you happy with Masked and Anonymous?

No. Whatever vision I had for that movie, that never could’ve carried to the screen. When you want to make a film and you’re using outside money, there’s just too many people you have to listen to.

I love that film.

I’m glad some people like it. I know people who do. There’s some performances in there. John Goodman. Isn’t he great? And Jessica Lange. Everybody was really good in it. Everybody except me. Ha-ha! I had no business being in it, to tell you the truth. What’s her name, Cate Blanchett [among the actors who played Dylan in I’m Not There], should’ve played the character that I played. It probably would’ve been a hit movie.

Will there be a Chronicles 2?

Oh, let’s hope so. I’m always working on parts of it. But the last Chronicles I did all by myself. I’m not even really so sure I had a proper editor for that. I don’t want really to say too much about that. But it’s a lot of work. I don’t mind writing it, but it’s the rereading it and the time it takes to reread it – that for me is difficult.

You’ve said before there are certain things you just don’t remember. I came away from Chronicles thinking that you remember almost everything. Why didn’t you ever talk before about that life of the mind you’ve gone through?

It’s not like I have a great memory. I remember what I want to remember. And what I want to forget, I forget. When you’re writing like that, it’s just kind of like one thing leads to another and another, you just keep opening doors and sliding in and finding a way out. It’s like links in a chain – you make connections as you go along.

In recent years, you’ve received numerous high honors, including one recently at the White House, where you were presented with a Medal of Freedom. You weren’t always comfortable with this sort of event. What makes you more accepting now of these laurels?

I turn down far more of those medals and honors than I pick up. They come in from all over the place – all parts of the world. Most of them will get turned down because I can’t physically be there to get them all. But every once in a while, there’s something that is important, an incredibly high honor that I would never have dreamed to be receiving, like the Medal of Freedom. There’s no way I would turn that down.

Do you accept the awards in part for your family, for your posterity?

I accept them for myself and myself only. And I don’t think about it any other way, and I don’t waste a lot of time overthinking it. It’s an incredible honor.

Receiving the Medal of Freedom had to be a bit of a thrill.

Oh, of course it’s a thrill! I mean, who wouldn’t want to get a letter from the White House? And the kind of people they were putting me in the category with was just amazing. People like John Glenn and Madeleine Albright, Toni Morrison and Pat Summitt, John Doer, William Foege and some others, too. These people who have done incredible things and have outstanding achievements. Pat Summitt alone has won more basketball games with her teams than any NCAA coach. John Glenn, we all know what he did. And Toni Morrison is as good as it gets. I loved spending time with them. What’s the alternative? Hanging around with hedge-fund hucksters or Hollywood gigolos? You know what I mean?

The Medal of Freedom, it’s an encircled star on a ribbon that hangs around your neck?

Yeah, I guess so. You should’ve told me you wanted to see it. I’d’ve brought it by and you could look at it, if you wanted.

Maybe next time.

Yeah. Sure, next time.

In July 2009, the police picked you up in Long Branch, New Jersey, while you were on a walk, supposedly looking for Bruce Springsteen’s old home. What happened on that occasion?

We were staying at a hotel. The bus was pulling out; I just decided I’d go for a walk. It was raining, and I guess that in that neck of the woods, they’re not used to seeing people walking in the rain. I was the only one on the street. Somebody saw me out of a window and reported me. Next thing I know, a cop car pulled up and asked me for ID. Well, I didn’t have any [laughs]. I wear so many changes of clothes all the time. The woman who was the police officer, she didn’t know me. Because most people don’t. They’ve heard the name. I might be in a place, nobody knows me. Right? All of a sudden, somebody will walk in who knows me, and I’ll have to tell e verybody in the p lace, and then . . . it gets uncomfortable.

That’s the side of people I see. People like to betray people. There’s something in people that they just want to betray somebody. “That’s him over there.” They want to deliver you up. Like they delivered Jesus. They want to be the one to do it. There’s something in people that’s just like that. I’ve experienced that. A lot.

Before we end the conversation, I want to ask about the controversy over your quotations in your songs from the works of other writers, such as Japanese author Junichi Saga’s Confessions of a Yakuza, and the Civil War poetry of Henry Timrod. Some critics say that you didn’t cite your sources clearly. Yet in folk and jazz, quotation is a rich and enriching tradition. What’s your response to those kinds of charges?

Oh, yeah, in folk and jazz, quotation is a rich and enriching tradition. That certainly is true. It’s true for everybody, but me. I mean, everyone else can do it but not me. There are different rules for me. And as far as Henry Timrod is concerned, have you even heard of him? Who’s been reading him lately? And who’s pushed him to the forefront? Who’s been making you read him? And ask his descendants what they think of the hoopla. And if you think it’s so easy to quote him and it can help your work, do it yourself and see how far you can get. Wussies and pussies complain about that stuff. It’s an old thing – it’s part of the tradition. It goes way back. These are the same people that tried to pin the name Judas on me. Judas, the most hated name in human history! If you think you’ve been called a bad name, try to work your way out from under that. Yeah, and for what? For playing an electric guitar? As if that is in some kind of way equitable to betraying our Lord and delivering him up to be crucified. All those evil motherfuckers can rot in hell.

Seriously?

I’m working within my art form. It’s that simple. I work within the rules and limitations of it. There are authoritarian figures that can explain that kind of art form better to you than I can. It’s called songwriting. It has to do with melody and rhythm, and then after that, anything goes. You make everything yours. We all do it.

When those lines make their way into a song, you’re conscious of it happening?

Well, not really. But even if you are, you let it go. I’m not going to limit what I can say. I have to be true to the song. It’s a particular art form that has its own rules. It’s a different type of thing. All my stuff comes out of the folk tradition – it’s not necessarily akin to the pop world.

Do you find that sort of criticism irrelevant, or silly?

I try to get past all that. I have to. When you ask me if I find criticism of my work irrelevant or silly, no, not if it’s constructive. If someone could point out here or there where my work could be improved upon, I guess I’d be willing to listen. The people who are obsessed with criticism – it’s not honest criticism. They are not the people who I play to anyway.

But surely you’ve heard about this particular controversy?

People have tried to stop me every inch of the way. They’ve always had bad stuff to say about me. Newsweek magazine l it the fuse way back when. Newsweek printed that some kid from New Jersey wrote “Blowin’ in the Wind” and it wasn’t me at all. And when that didn’t fly, people accused me of stealing the melody from a 16th-century Protestant hymn. And when that didn’t work, they said they made a mistake and it was really an old Negro spiritual. So what’s so different? It’s gone on for so long I might not be able to live without it now. Fuck ’em. I’ll see them all in their graves. Everything people say about you or me, they are saying about themselves. They’re telling about themselves. Ever notice that? In my case, there’s a whole world of scholars, professors and Dylanologists, and everything I do affects them in some way. And, you know, in some ways, I’ve given them life. They’d be nowhere without me.

And inspiration.

No, they’re not good for that.

The flip side of people being critical . . .

Yeah, to hold someone in high admiration. [laughs].

The flip side is, there’s also the audience that really loves you.

Of course. They think they do. They love the music and songs I play, not me.

Why do you say that?

Because that’s the way people are. People say they love a lot of things, but they really don’t. It’s just a word that’s been overused. When you put your life on the line for somebody, that’s love. But you’ll never know it until you’re in the moment. When someone will die for you, that’s love, too.