Bob Dylan was honored by MusiCares, the charity organization that aids musicians in need, at the Los Angeles Convention Center on Friday night. After performances by artists including Tom Jones, Sheryl Crow, Neil Young, Beck, Jackson Browne and others, Dylan himself took a rare opportunity in the spotlight to deliver a 30-plus-minute acceptance speech.

Expansive, funny and insightful, Dylan didn't pull any punches, calling out songwriters who had criticized his work while indicting Nashville and commercial country music.

He was introduced by former President Jimmy Carter, and walked out to a standing ovation. After thanking the organizers, Dylan referred to his notes and began by saying, "I'm going to read some of this."

Because of moments of applause, and some echoey acoustics, a few of Dylan's words were inaudible on the recording I've consulted, and I've noted as such. Though it upsets him to hear it (see below), Dylan does sometimes mumble and slur his words.

Bob Dylan's MusiCares person of the year acceptance speech:

__

I'm glad for my songs to be honored like this. But you know, they didn't get here by themselves. It's been a long road and it's taken a lot of doing. These songs of mine, they're like mystery stories, the kind that Shakespeare saw when he was growing up. I think you could trace what I do back that far. They were on the fringes then, and I think they're on the fringes now. And they sound like they've been on the hard ground.

I should mention a few people along the way who brought this about. I know I should mention John Hammond, great talent scout for Columbia Records. He signed me to that label when I was nobody. It took a lot of faith to do that, and he took a lot of ridicule, but he was his own man and he was courageous. And for that, I'm eternally grateful. The last person he discovered before me was Aretha Franklin, and before that Count Basie, Billie Holiday and a whole lot of other artists. All noncommercial artists.

Trends did not interest John, and I was very noncommercial but he stayed with me. He believed in my talent and that's all that mattered. I can't thank him enough for that.

Lou Levy runs Leeds Music, and they published my earliest songs, but I didn't stay there too long. Levy himself, he went back a long ways. He signed me to that company and recorded my songs and I sang them into a tape recorder. He told me outright, there was no precedent for what I was doing, that I was either before my time or behind it. And if I brought him a song like "Stardust," he'd turn it down because it would be too late.

He told me that if I was before my time -- and he didn't really know that for sure -- but if it was happening and if it was true, the public would usually take three to five years to catch up -- so be prepared. And that did happen. The trouble was, when the public did catch up I was already three to five years beyond that, so it kind of complicated it. But he was encouraging, and he didn't judge me, and I'll always remember him for that.

Artie Mogull at Witmark Music signed me next to his company, and he told me to just keep writing songs no matter what, that I might be on to something. Well, he too stood behind me, and he could never wait to see what I'd give him next. I didn't even think of myself as a songwriter before then. I'll always be grateful for him also for that attitude.

I also have to mention some of the early artists who recorded my songs very, very early, without having to be asked. Just something they felt about them that was right for them. I've got to say thank you to Peter, Paul and Mary, who I knew all separately before they ever became a group. I didn't even think of myself as writing songs for others to sing but it was starting to happen and it couldn't have happened to, or with, a better group.

They took a song of mine that had been recorded before that was buried on one of my records and turned it into a hit song. Not the way I would have done it -- they straightened it out. But since then hundreds of people have recorded it and I don't think that would have happened if it wasn't for them. They definitely started something for me.

The Byrds, the Turtles, Sonny & Cher -- they made some of my songs Top 10 hits but I wasn't a pop songwriter and I really didn't want to be that, but it was good that it happened. Their versions of songs were like commercials, but I didn't really mind that because 50 years later my songs were being used in the commercials. So that was good too. I was glad it happened, and I was glad they'd done it.

Pervis Staples and the Staple Singers -- long before they were on Stax they were on Epic and they were one of my favorite groups of all time. I met them all in '62 or '63. They heard my songs live and Pervis wanted to record three or four of them and he did with the Staples Singers. They were the type of artists that I wanted recording my songs.

Nina Simone. I used to cross paths with her in New York City in the Village Gate nightclub. These were the artists I looked up to. She recorded some of my songs that she [inaudible] to me. She was an overwhelming artist, piano player and singer. Very strong woman, very outspoken. That she was recording my songs validated everything that I was about.

Oh, and can't forget Jimi Hendrix. I actually saw Jimi Hendrix perform when he was in a band called Jimmy James and the Blue Flames -- something like that. And Jimi didn't even sing. He was just the guitar player. He took some small songs of mine that nobody paid any attention to and pumped them up into the outer limits of the stratosphere and turned them all into classics. I have to thank Jimi, too. I wish he was here.

Johnny Cash recorded some of my songs early on, too, up in about '63, when he was all skin and bones. He traveled long, he traveled hard, but he was a hero of mine. I heard many of his songs growing up. I knew them better than I knew my own. "Big River," "I Walk the Line."

"How high's the water, Mama?" I wrote "It's Alright Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)" with that song reverberating inside my head. I still ask, "How high is the water, mama?" Johnny was an intense character. And he saw that people were putting me down playing electric music, and he posted letters to magazines scolding people, telling them to shut up and let him sing.

In Johnny Cash's world -- hardcore Southern drama -- that kind of thing didn't exist. Nobody told anybody what to sing or what not to sing. They just didn't do that kind of thing. I'm always going to thank him for that. Johnny Cash was a giant of a man, the man in black. And I'll always cherish the friendship we had until the day there is no more days.

Oh, and I'd be remiss if I didn't mention Joan Baez. She was the queen of folk music then and now. She took a liking to my songs and brought me with her to play concerts, where she had crowds of thousands of people enthralled with her beauty and voice.

People would say, "What are you doing with that ragtag scrubby little waif?" And she'd tell everybody in no uncertain terms, "Now you better be quiet and listen to the songs." We even played a few of them together. Joan Baez is as tough-minded as they come. Love. And she's a free, independent spirit. Nobody can tell her what to do if she doesn't want to do it. I learned a lot of things from her. A woman with devastating honesty. And for her kind of love and devotion, I could never pay that back.

These songs didn't come out of thin air. I didn't just make them up out of whole cloth. Contrary to what Lou Levy said, there was a precedent. It all came out of traditional music: traditional folk music, traditional rock 'n' roll and traditional big-band swing orchestra music.

I learned lyrics and how to write them from listening to folk songs. And I played them, and I met other people that played them back when nobody was doing it. Sang nothing but these folk songs, and they gave me the code for everything that's fair game, that everything belongs to everyone.

For three or four years all I listened to were folk standards. I went to sleep singing folk songs. I sang them everywhere, clubs, parties, bars, coffeehouses, fields, festivals. And I met other singers along the way who did the same thing and we just learned songs from each other. I could learn one song and sing it next in an hour if I'd heard it just once.

If you sang "John Henry" as many times as me -- "John Henry was a steel-driving man / Died with a hammer in his hand / John Henry said a man ain't nothin' but a man / Before I let that steam drill drive me down / I'll die with that hammer in my hand."

If you had sung that song as many times as I did, you'd have written "How many roads must a man walk down?" too.

Big Bill Broonzy had a song called "Key to the Highway." "I've got a key to the highway / I'm booked and I'm bound to go / Gonna leave here runnin' because walking is most too slow." I sang that a lot. If you sing that a lot, you just might write,

Georgia Sam he had a bloody nose

Welfare Department they wouldn’t give him no clothes

He asked poor Howard where can I go

Howard said there’s only one place I know

Sam said tell me quick man I got to run

Howard just pointed with his gun

And said that way down on Highway 61

You'd have written that too if you'd sang "Key to the Highway" as much as me.

"Ain't no use sit 'n cry / You'll be an angel by and by / Sail away, ladies, sail away." "I'm sailing away my own true love." "Boots of Spanish Leather" -- Sheryl Crow just sung that.

"Roll the cotton down, aw, yeah, roll the cotton down / Ten dollars a day is a white man's pay / A dollar a day is the black man's pay / Roll the cotton down." If you sang that song as many times as me, you'd be writing "I ain't gonna work on Maggie's farm no more," too.

I sang a lot of "come all you" songs. There's plenty of them. There's way too many to be counted. "Come along boys and listen to my tale / Tell you of my trouble on the old Chisholm Trail." Or, "Come all ye good people, listen while I tell / the fate of Floyd Collins a lad we all know well / The fate of Floyd Collins, a lad we all know well."

"Come all ye fair and tender ladies / Take warning how you court your men / They're like a star on a summer morning / They first appear and then they're gone again." "If you'll gather 'round, people / A story I will tell / 'Bout Pretty Boy Floyd, an outlaw / Oklahoma knew him well."

If you sung all these "come all ye" songs all the time, you'd be writing, "Come gather 'round people where ever you roam, admit that the waters around you have grown / Accept that soon you'll be drenched to the bone / If your time to you is worth saving / And you better start swimming or you'll sink like a stone / The times they are a-changing."

You'd have written them too. There's nothing secret about it. You just do it subliminally and unconsciously, because that's all enough, and that's all I sang. That was all that was dear to me. They were the only kinds of songs that made sense.

"When you go down to Deep Ellum keep your money in your socks / Women in Deep Ellum put you on the rocks." Sing that song for a while and you just might come up with, "When you're lost in the rain in Juarez and it's Easter time too / And your gravity fails and negativity don't pull you through / Don’t put on any airs / When you’re down on Rue Morgue Avenue / They got some hungry women there / And they really make a mess outta you."

All these songs are connected. Don't be fooled. I just opened up a different door in a different kind of way. It's just different, saying the same thing. I didn't think it was anything out of the ordinary.

Well you know, I just thought I was doing something natural, but right from the start, my songs were divisive for some reason. They divided people. I never knew why. Some got angered, others loved them. Didn't know why my songs had detractors and supporters. A strange environment to have to throw your songs into, but I did it anyway.

Last thing I thought of was who cared about what song I was writing. I was just writing them. I didn't think I was doing anything different. I thought I was just extending the line. Maybe a little bit unruly, but I was just elaborating on situations. Maybe hard to pin down, but so what? A lot of people are hard to pin down. You've just got to bear it. I didn't really care what Lieber and Stoller thought of my songs.

They didn't like 'em, but Doc Pomus did. That was all right that they didn't like 'em, because I never liked their songs either. "Yakety yak, don't talk back." "Charlie Brown is a clown," "Baby I'm a hog for you." Novelty songs. They weren't saying anything serious. Doc's songs, they were better. "This Magic Moment." "Lonely Avenue." Save the Last Dance for Me.

Those songs broke my heart. I figured I'd rather have his blessings any day than theirs.

Ahmet Ertegun didn't think much of my songs, but Sam Phillips did. Ahmet founded Atlantic Records. He produced some great records: Ray Charles, Ray Brown, just to name a few.

There were some great records in there, no question about it. But Sam Phillips, he recorded Elvis and Jerry Lee, Carl Perkins and Johnny Cash. Radical eyes that shook the very essence of humanity. Revolution in style and scope. Heavy shape and color. Radical to the bone. Songs that cut you to the bone. Renegades in all degrees, doing songs that would never decay, and still resound to this day. Oh, yeah, I'd rather have Sam Phillips' blessing any day.

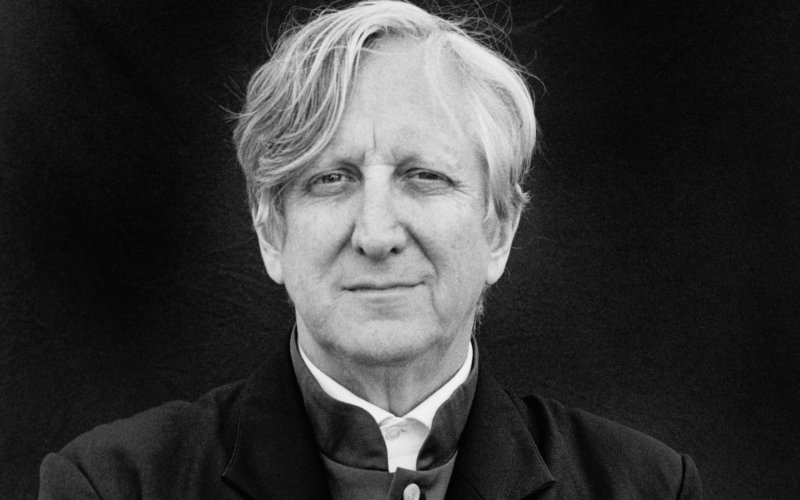

Bob Dylan, the 2015 MusiCares Person of the Year, speaks of his life and music to the crowd. (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Merle Haggard didn't even think much of my songs. I know he didn't. He didn't say that to me, but I know [inaudible]. Buck Owens did, and he recorded some of my early songs. Merle Haggard -- "Mama Tried," "The Bottle Let Me Down," "I'm a Lonesome Fugitive." I can't imagine Waylon Jennings singing "The Bottle Let Me Down."

"Together Again"? That's Buck Owens, and that trumps anything coming out of Bakersfield. Buck Owens and Merle Haggard? If you have to have somebody's blessing -- you figure it out.

Oh, yeah. Critics have been giving me a hard time since Day One. Critics say I can't sing. I croak. Sound like a frog. Why don't critics say that same thing about Tom Waits? Critics say my voice is shot. That I have no voice. What don't they say those things about Leonard Cohen? Why do I get special treatment? Critics say I can't carry a tune and I talk my way through a song. Really? I've never heard that said about Lou Reed. Why does he get to go scot-free?

What have I done to deserve this special attention? No vocal range? When's the last time you heard Dr. John? Why don't you say that about him? Slur my words, got no diction. Have you people ever listened to Charley Patton or Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters. Talk about slurred words and no diction. [Inaudible] doesn't even matter.

"Why me, Lord?" I would say that to myself.

Critics say I mangle my melodies, render my songs unrecognizable. Oh, really? Let me tell you something. I was at a boxing match a few years ago seeing Floyd Mayweather fight a Puerto Rican guy. And the Puerto Rican national anthem, somebody sang it and it was beautiful. It was heartfelt and it was moving.

After that it was time for our national anthem. And a very popular soul-singing sister was chosen to sing. She sang every note -- that exists, and some that don't exist. Talk about mangling a melody. You take a one-syllable word and make it last for 15 minutes? She was doing vocal gymnastics like she was on a trapeze act. But to me it was not funny.

Where were the critics? Mangling lyrics? Mangling a melody? Mangling a treasured song? No, I get the blame. But I don't really think I do that. I just think critics say I do.

Sam Cooke said this when told he had a beautiful voice: He said, "Well that's very kind of you, but voices ought not to be measured by how pretty they are. Instead they matter only if they convince you that they are telling the truth." Think about that the next time you [inaudible].

Times always change. They really do. And you have to always be ready for something that's coming along and you never expected it. Way back when, I was in Nashville making some records and I read this article, a Tom T. Hall interview. Tom T. Hall, he was bitching about some kind of new song, and he couldn't understand what these new kinds of songs that were coming in were about.

Now Tom, he was one of the most preeminent songwriters of the time in Nashville. A lot of people were recording his songs and he himself even did it. But he was all in a fuss about James Taylor, a song James had called "Country Road." Tom was going off in this interview -- "But James don't say nothing about a country road. He's just says how you can feel it on the country road. I don't understand that."

Now some might say Tom is a great songwriter. I'm not going to doubt that. At the time he was doing this interview I was actually listening to a song of his on the radio.

It was called "I Love." I was listening to it in a recording studio, and he was talking about all the things he loves, an everyman kind of song, trying to connect with people. Trying to make you think that he's just like you and you're just like him. We all love the same things, and we're all in this together. Tom loves little baby ducks, slow-moving trains and rain. He loves old pickup trucks and little country streams. Sleeping without dreams. Bourbon in a glass. Coffee in a cup. Tomatoes on the vine, and onions.

Now listen, I'm not ever going to disparage another songwriter. I'm not going to do that. I'm not saying it's a bad song. I'm just saying it might be a little overcooked. But, you know, it was in the top 10 anyway. Tom and a few other writers had the whole Nashville scene sewed up in a box. If you wanted to record a song and get it in the top 10 you had to go to them, and Tom was one of the top guys. They were all very comfortable, doing their thing.

This was about the time that Willie Nelson picked up and moved to Texas. About the same time. He's still in Texas. Everything was very copacetic. Everything was all right until -- until -- Kristofferson came to town. Oh, they ain't seen anybody like him. He came into town like a wildcat, flew his helicopter into Johnny Cash's backyard like a typical songwriter. And he went for the throat. "Sunday Morning Coming Down."

Well, I woke up Sunday morning

With no way to hold my head that didn't hurt.

And the beer I had for breakfast wasn't bad

So I had one more for dessert

Then I fumbled through my closet

Found my cleanest dirty shirt

Then I washed my face and combed my hair

And stumbled down the stairs to meet the day.

You can look at Nashville pre-Kris and post-Kris, because he changed everything. That one song ruined Tom T. Hall's poker parties. It might have sent him to the crazy house. God forbid he ever heard any of my songs.

You walk into the room

With your pencil in your hand

You see somebody naked

You say, “Who is that man?”

You try so hard

But you don’t understand

Just what you're gonna say

When you get home

You know something is happening here

But you don’t know what it is

Do you, Mister Jones?

If "Sunday Morning Coming Down" rattled Tom's cage, sent him into the looney bin, my song surely would have made him blow his brains out, right there in the minivan. Hopefully he didn't hear it.

I just released an album of standards, all the songs usually done by Michael Buble, Harry Connick Jr., maybe Brian Wilson's done a couple, Linda Ronstadt done 'em. But the reviews of their records are different than the reviews of my record.

In their reviews no one says anything. In my reviews, [inaudible] they've got to look under every stone when it comes to me. They've got to mention all the songwriters' names. Well that's OK with me. After all, they're great songwriters and these are standards. I've seen the reviews come in, and they'll mention all the songwriters in half the review, as if everybody knows them. Nobody's heard of them, not in this time, anyway. Buddy Kaye, Cy Coleman, Carolyn Leigh, to name a few.

But, you know, I'm glad they mention their names, and you know what? I'm glad they got their names in the press. It might have taken some time to do it, but they're finally there. I can only wonder why it took so long. My only regret is that they're not here to see it.

Traditional rock 'n' roll, we're talking about that. It's all about rhythm. Johnny Cash said it best: "Get rhythm. Get rhythm when you get the blues." Very few rock 'n' roll bands today play with rhythm. They don't know what it is. Rock 'n' roll is a combination of blues, and it's a strange thing made up of two parts. A lot of people don't know this, but the blues, which is an American music, is not what you think it is. It's a combination of Arabic violins and Strauss waltzes working it out. But it's true.

The other half of rock 'n' roll has got to be hillbilly. And that's a derogatory term, but it ought not to be. That's a term that includes the Delmore Bros., Stanley Bros., Roscoe Holcomb, Clarence Ashley ... groups like that. Moonshiners gone berserk. Fast cars on dirt roads. That's the kind of combination that makes up rock 'n' roll, and it can't be cooked up in a science laboratory or a studio.

You have to have the right kind of rhythm to play this kind of music. If you can't hardly play the blues, how do you [inaudible] those other two kinds of music in there? You can fake it, but you can't really do it.

Critics have made a career out of accusing me of having a career of confounding expectations. Really? Because that's all I do. That's how I think about it. Confounding expectations.

"What do you do for a living, man?"

"Oh, I confound expectations."

You're going to get a job, the man says, "What do you do?" "Oh, confound expectations.: And the man says, "Well, we already have that spot filled. Call us back. Or don't call us, we'll call you." Confounding expectations. What does that mean? 'Why me, Lord? I'd confound them, but I don't know how to do it.'

The Blackwood Bros. have been talking to me about making a record together. That might confound expectations, but it shouldn't. Of course it would be a gospel album. I don't think it would be anything out of the ordinary for me. Not a bit. One of the songs I'm thinking about singing is "Stand By Me" by the Blackwood Brothers. Not "Stand By Me" the pop song. No. The real "Stand By Me."

The real one goes like this:

When the storm of life is raging / Stand by me / When the storm of life is raging / Stand by me / When the world is tossing me / Like a ship upon the sea / Thou who rulest wind and water / Stand by me

In the midst of tribulation / Stand by me / In the midst of tribulation / Stand by me / When the hosts of hell assail / And my strength begins to fail / Thou who never lost a battle / Stand by me

In the midst of faults and failures / Stand by me / In the midst of faults and failures / Stand by me / When I do the best I can / And my friends don't understand / Thou who knowest all about me / Stand by me

That's the song. I like it better than the pop song. If I record one by that name, that's going to be the one. I'm also thinking of recording a song, not on that album, though: "Oh Lord, Please Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood."

Anyway, why me, Lord. What did I do?

Anyway, I'm proud to be here tonight for MusiCares. I'm honored to have all these artists singing my songs. There's nothing like that. Great artists. [applause, inaudible]. They're all singing the truth, and you can hear it in their voices.

I'm proud to be here tonight for MusiCares. I think a lot of this organization. They've helped many people. Many musicians who have contributed a lot to our culture. I'd like to personally thank them for what they did for a friend of mine, Billy Lee Riley. A friend of mine who they helped for six years when he was down and couldn't work. Billy was a son of rock 'n' roll, obviously.

He was a true original. He did it all: He played, he sang, he wrote. He would have been a bigger star but Jerry Lee came along. And you know what happens when someone like that comes along. You just don't stand a chance.

So Billy became what is known in the industry -- a condescending term, by the way -- as a one-hit wonder. But sometimes, just sometimes, once in a while, a one-hit wonder can make a more powerful impact than a recording star who's got 20 or 30 hits behind him. And Billy's hit song was called "Red Hot," and it was red hot. It could blast you out of your skull and make you feel happy about it. Change your life.

He did it with style and grace. You won't find him in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. He's not there. Metallica is. Abba is. Mamas and the Papas -- I know they're in there. Jefferson Airplane, Alice Cooper, Steely Dan -- I've got nothing against them. Soft rock, hard rock, psychedelic pop. I got nothing against any of that stuff, but after all, it is called the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Billy Lee Riley is not there. Yet.

I'd see him a couple times a year and we'd always spent time together and he was on a rockabilly festival nostalgia circuit, and we'd cross paths now and again. We'd always spend time together. He was a hero of mine. I'd heard "Red Hot." I must have been only 15 or 16 when I did and it's impressed me to this day.

I never grow tired of listening to it. Never got tired of watching Billy Lee perform, either. We spent time together just talking and playing into the night. He was a deep, truthful man. He wasn't bitter or nostalgic. He just accepted it. He knew where he had come from and he was content with who he was.

And then one day he got sick. And like my friend John Mellencamp would sing -- because John sang some truth today -- one day you get sick and you don't get better. That's from a song of his called "Life is Short Even on Its Longest Days." It's one of the better songs of the last few years, actually. I ain't lying.

And I ain't lying when I tell you that MusiCares paid for my friend's doctor bills, and helped him to get spending money. They were able to at least make his life comfortable, tolerable to the end. That is something that can't be repaid. Any organization that would do that would have to have my blessing.

I'm going to get out of here now. I'm going to put an egg in my shoe and beat it. I probably left out a lot of people and said too much about some. But that's OK. Like the spiritual song, 'I'm still just crossing over Jordan too.' Let's hope we meet again. Sometime. And we will, if, like Hank Williams said, "the good Lord willing and the creek don't rise."