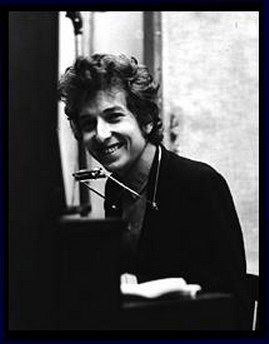

The artwork for Bob Dylan’s album The Basement Tapes, recorded in 1967 but not officially released until 1975, features Dylan and the members of The Band playing in a basement surrounded by circus entertainers – belly dancers, fire-eaters, midgets, etc. Just as the album’s music found Dylan rejecting The Voice of a Generation mantle that had been bestowed upon him in favor of an older and more elemental approach, so did the art work symbolize the beginning of a new phase of Dylan’s career – that of the traveling entertainer, the minstrel, the road-show trooper.

Dylan is now nearing 2000 performances on the never-ending tour that supposedly began in 1988. But it is hard to imagine that he’s played to many crowds larger than the one that awaited him Sunday night at the Austin City Limits festival. As the other stages shut down – Wilco, the Decemberists, Ziggy Marley – everyone from high school kids with their cell phones to grandparents with their lawn chairs flocked toward the far end of Zilker Park where Dylan was set to perform.

Driving over that morning, I listened to classic Dylan and recent Dylan to prepare myself for what has become of his voice. The young Dylan was a master of pre-rap rhythm and hillbilly melodic nuance with punk attitude to burn – a truly great rock and roll singer. The old Dylan croaks along like a frog bumping his ass on the ground, which makes it all the remarkable that he is still releasing cool and essential albums like last year’s Modern Times.

But it was no less a shock when Dylan launched into the first tune, “Rainy Day Woman,” and out came a strange and painful sound. This was way beyond the proverbial frog in the throat – more like an old Delta blues singer who’d just gargled with Sterno. The band, anchored by Austinites Tony Garnier on bass and Denny Freeman on guitar, began to find its groove on the blues “Watchin’ the River Flow.” The set list alternated old favorites – “It Ain’t Me, Babe,” “Tangled Up In Blue” -- with songs from the new album, “Spirit On the Water,” “The Levee’s Gonna Break.”

By the time they got to “Highway 61,” another blues, the band was really locked in the groove and Dylan’s voice seemed to be loosening up. Laying on my back on the grass about 300 yards from the stage, I convinced myself that it didn’t matter if this was a great show or not. What mattered is that he is still out there doing it, and all these kids will be able to tell their grandchildren that they saw the legendary Bob Dylan in his white straw hat and white striped trousers – the stage uniform of a trooper.

But then Dylan pulled a surprise; on “Nettie Moore,” a folksy ballad from Modern Times, he put his voice way up front in the mix, reveling in its wrecked glory, as a violin cooed gently in the background The result somehow sounded both timeless and brand new, an instant classic. “Ballad of a Thin Man” found Dylan snarling with renewed vigor from behind the keyboard. The first encore, the Chuck Berryish “Thunder on the Mountain,” had the college girls up and swirling like their mothers at a rock festival from way back in the day.

“Like a Rolling Stone” came next, of course. Forty years ago, this song asked a generation that imagined it was breaking loose from all the old rules, “How does it feel?” Now it could be the medical question one hears at one’s 40th high school reunion. “How does it feel?” Well, it hurts. And not just my aching back. My soul hurts, because the world is as fucked up as it ever was and our country is stuck in another war that should never have been started. It’s like we – our generation -- never learned a goddamn thing. Walking toward the exit, I thought that Dylan, the history buff, might have predicted as much. Human nature does not change. What matters is that the show must go on.

But then Dylan pulled another surprise: For the first time in the night, he spoke, introducing the members of the band in his antiquated, carnival-showman’s accent. And then he sang one of the most beautiful songs he’s ever written, “I Shall Be Released,” a prayer for spiritual and psychological liberation from the inevitable suffering that living brings. And suddenly, Dylan’s voice didn’t sound wrecked anymore – it sounded, well, hopeful. Even more than that, it sounded human; not the voice of a generation, the voice of one man. And I walked out smiling into the night. – Rick Mitchell

Austin, Texas

September 16, 2007

| 1. | Rainy Day Women #12 & 35 (Bob on electric guitar) |

| 2. | It Ain't Me, Babe (Bob on electric guitar) |

| 3. | Watching The River Flow (Bob on electric guitar) |

| 4. | Spirit On The Water (Bob on electric keyboard and harp) |

| 5. | The Levee's Gonna Break (Bob on electric keyboard, Donnie on electric mandolin) |

| 6. | Tangled Up In Blue (Bob on electric keyboard and harp) |

| 7. | Things Have Changed (Bob on electric keyboard) |

| 8. | Workingman's Blues #2 (Bob on electric keyboard) |

| 9. | Highway 61 Revisited (Bob on electric keyboard) |

| 10. | Nettie Moore (Bob on electric keyboard and harp, Donnie on violin) |

| 11. | Summer Days (Bob on electric keyboard) |

| 12. | Ballad Of A Thin Man (Bob on electric keyboard and harp) |

| (encore) | |

| 13. | Thunder On The Mountain (Bob on electric keyboard) |

| 14. | Like A Rolling Stone (Bob on electric keyboard) |

| 15. | I Shall Be Released (Bob on electric keyboard and harp) |

0 comentarios